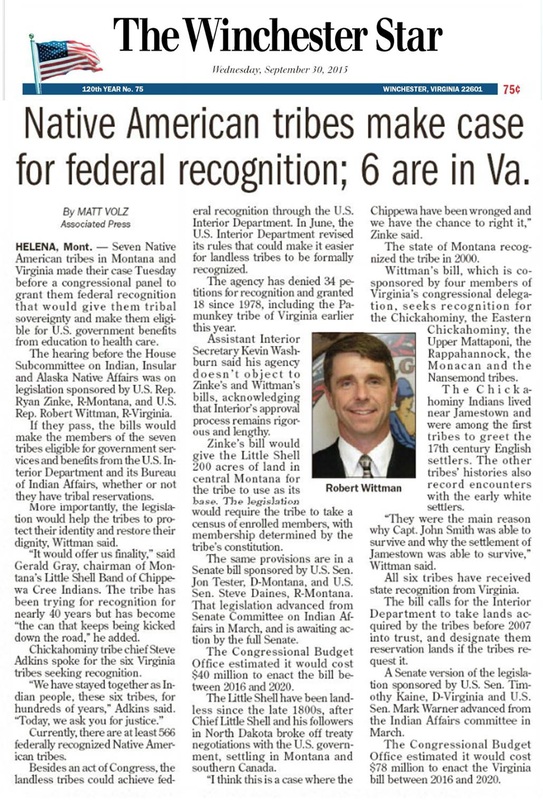

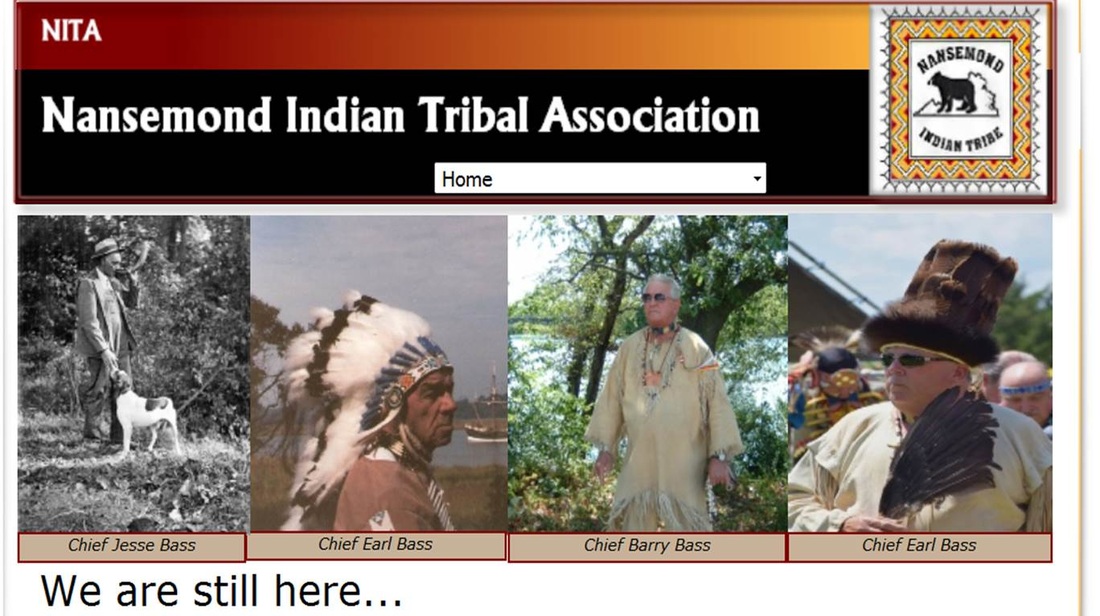

| House and Senate Transcript, Bills and Resolutions regarding Federal Recognition for Virginia Indians. Hon. James. P. Moran Congressional Record Introduction of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes Of Virginia Federal Recognition Act : quoted article "Mr. MORAN. Mr. Speaker, today I am introducing the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. This is the sixth time I have introduced legislation that would grant federal recognition to six Indian tribes in Virginia: the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond. Similar measures passed the House and the Senate Indian Affairs Committee during the 110th and 111th Sessions of Congress. Unfortunately, both measures were ultimately defeated when the objections of a few Senators were not overridden. The impasse in Congress and the demeaning and dysfunctional acknowledgement process at the Bureau of Indian Affairs only com-pound the grave injustices this legislation seeks to redress. It also compels me to continue this cause and reintroduce this legislation today. The injustices extend back in time for hundreds of years, back to the establishment of the first permanent English settlement in America at Jamestown. For the Members of these tribes are the descendents of the great Powhatan Confederacy who greeted the English and provided food and assistance that ensured the settlers’ early survival. Four years ago, America celebrated the 400th anniversary of the settlement of James-town. But it was not a celebration for Native American descendents of Pocahontas, for they have yet to be recognized by our federal government. Unlike most Native American tribes that were officially recognized when they signed peace treaties with the federal government, Virginia’s six Native American tribes made their peace with the Kings of England. Most notable among these was the Treaty of 1677 between these tribes and King Charles II. This treaty has been recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia every year for the past 334 years when the Governor accepts tribute from the tribes in a ceremony now celebrated at the Commonwealth Capitol. I had the honor of attending the one of what I understand is the longest celebrated treaty recognition ceremony in the United States. The forefathers of the tribal leaders who gather on Thanksgiving in Richmond were the first to welcome the English, and during the first few years of settlement, ensured their survival. Had the tribes not assisted those early settlers, they would not have survived. Time has not been kind to the tribes, however. As was the case for most Native American tribes, as the settlement prospered and grew, the tribes suffered. Those who resisted quickly be-came subdued, were pushed off their historic lands, and, up through much of the 20th Century, were denied full rights as U.S. citizens. Despite their devastating loss of land and population, the Virginia tribes survived, preserving their heritage and their identity. Their story of survival spans four centuries of racial hostility and coercive state and state-sanctioned actions. The Virginia tribes’ history, however, diverges from that of most Native Americans in two unique ways. The first explains why the Virginia tribes were never recognized by the federal government; the second explains why congressional action is needed today. First, by the time the federal government was established in 1789, the Virginia tribes were in no position to seek recognition. They had already lost control of their land, withdrawn into isolated communities and stripped of most of their rights. Lacking even the rights granted by the English Kings, and our own Bill of Rights, federal recognition was nowhere within their reach. The second unique circumstance for the Virginia tribes is what they experienced at the hands of the Commonwealth government during the first half of the 20th Century. It has been called ‘‘paper genocide.’’ At a time when the federal government granted Native Americans the right to vote, Virginia’s elected officials adopted racially hostile laws targeted at those classes of people who did not fit into the dominant white society, and with fanatical efficiency, altered and destroyed the records of Virginia’s Native Americans. Virginia’s political elite sought to expunge the records of anyone other than themselves who could hold the claim that they were the descendent of Pocahontas. Pocahontas’ marriage to John Rolfe created an uncomfortable circumstance for John Rolfe’s descendents who populated Virginia’s aristocratic elite and who maintained that all non-whites were part of ‘‘the inferior Negroid race.’’ "I urge my colleagues to support this legislation and bring closure to centuries of in-justice Virginia’s Native American tribes have experienced." | Bills & Resolutions There is no doubt that the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Monacan, the Nansemond, the Rappahannock and the Upper Mattaponi tribes exist. These tribes have existed on a continuous basis since be-fore the first European settlers stepped foot in America. They are here with us today. But the federal government continues to act as if they do not.

With great hypocrisy, Virginia’s ruling elite pushed policies that culminated with the enactment of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This act directed Commonwealth officials, and zealots like Walter Plecker, to destroy Commonwealth and local courthouse records and reclassify in Orwellian fashion all non-whites as ‘‘colored.’’ It targeted Native Americans with a vengeance, denying Native Americans in Virginia their identity. To call oneself a ‘‘Native American’’ in Virginia was to risk a jail sentence of up to one year. In defiance of the law, members of Virginia’s tribes traveled out of state to obtain marriage licenses or to serve their country in wartime. The law remained in effect until it was struck down in federal court in 1967. In that intervening period between 1924 and 1967, Commonwealth officials waged a war to destroy all public and many private records that affirmed the existence of Native Americans in Virginia. Historians have affirmed that no other state compares to Virginia’s efforts to eradicate its citizens’ Indian identity. All of Virginia’s state-recognized tribes have filed petitions with the Bureau of Acknowledgment seeking federal recognition. But it is a very heavy burden the Virginia tribes will have to overcome, and one fraught with complications that officials from the bureau have acknowledged may never be resolved in their lifetime. The acknowledgment process is already expensive, subject to unreasonable delays, and lacking in dignity. Virginia’s paper genocide only further complicates these tribes’ quest for federal recognition, making it difficult to furnish corroborating state and official documents and aggravating the injustice already visited upon them. It was not until 1997, when Governor George Allen signed legislation directing Commonwealth agencies to correct their records, that the tribes were given the opportunity to correct official Commonwealth documents that had deliberately been altered to list them as ‘‘colored.’’ The law allows living members of the tribes to correct their records, but the law cannot correct the damage done to past generations or to recover documents that were purposely destroyed during the ‘‘Plecker Era.’’ In 1999, the Virginia General Assembly adopted a resolution calling upon Congress to enact legislation recognizing the Virginia tribes. I am pleased to have honored that re-quest, and beginning in 2000 and in subsequent sessions, Virginia’s Senators and I have introduced legislation to recognize the Virginia tribes. There is no doubt that the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Monacan, the Nansemond, the Rappahannock and the Upper Mattaponi tribes exist. These tribes have existed on a continuous basis since be-fore the first European settlers stepped foot in America. They are here with us today. But the federal government continues to act as if they do not. I know there is resistance in Congress to grant any Native American tribe federal recognition. And I can appreciate how the issue of gambling and its economic and moral dimensions has influenced many Members’ perspectives on tribal recognition issues. The six Virginia tribes are not seeking federal legislation so that they can build casinos. Under this legislation they cannot engage in gaming. The bill prohibits gambling on their lands. They find gambling offensive to their moral beliefs. They are seeking federal recognition because it is an urgent matter of justice and because elder members of their tribes, who were denied a public education and the economic opportunities available to most Americans, are suffering and should be entitled to the federal health and housing assistance available to federally recognized tribes. To underscore this point, the legislation includes language that would prevent the tribes from engaging in gaming on their federal land even if everyone else in Virginia were allowed to engage in Class III casino-type gaming. In the name of decency, fairness and humanity, I urge my colleagues to support this legislation and bring closure to centuries of in-justice Virginia’s Native American tribes have experienced." |

|

Click on the History Button to see Bills and Resolutions regarding Federal Recognition for Virginia Indians.

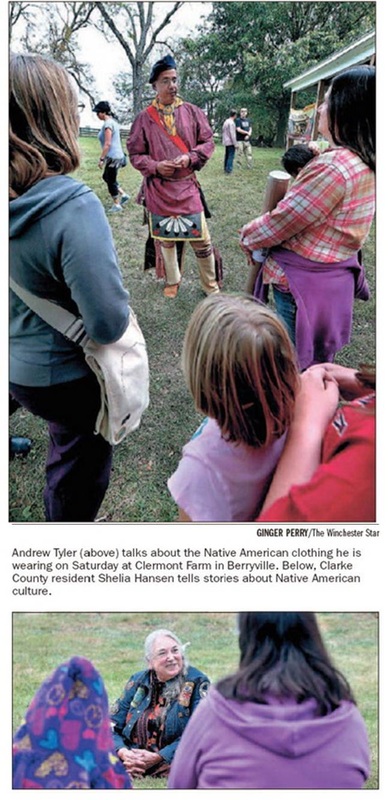

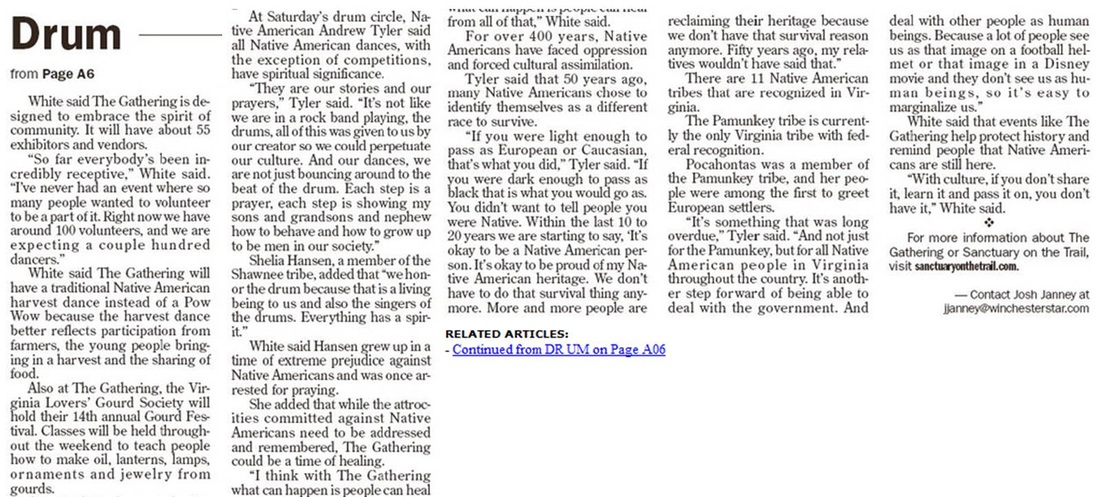

Thank you A'lice Myers-Hall Virginia Shawnee and Lenape Indian for your article in The Observer Magazine. We are grateful for your service as a military veteran to our country and for your volunteering now to help us connect communities to communities through The Gathering Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.

Thanks Winchester Star Reporter Josh Janney and Photographer Ginger Perry for covering this weekend's drum circle. You are helping preserve a culture and transform our futures. Thank you for giving voices to our stories.

|

The index table below shows various events that we have offered over the years.

Embrace the Spirit

Interest Topics

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed